The best urban legends are the ones that, after you’ve allowed yourself a few sceptical laughs at the absurdity of it all, creep into your mind and convince you that they could happen, after all. For his first foray into horror, Almodóvar has adapted Thierry Jonque’s novel Tarantula, but he seems to have these responses in the wrong order. And while this review may tiptoe around the finer details, this is purely to keep the surprises intact. So go and see the film, grumble at the irrationality of it all and then read this, eh?

The best urban legends are the ones that, after you’ve allowed yourself a few sceptical laughs at the absurdity of it all, creep into your mind and convince you that they could happen, after all. For his first foray into horror, Almodóvar has adapted Thierry Jonque’s novel Tarantula, but he seems to have these responses in the wrong order. And while this review may tiptoe around the finer details, this is purely to keep the surprises intact. So go and see the film, grumble at the irrationality of it all and then read this, eh?

To discover that the great director of Spanish melodrama (not to mention the most commercially successful director the country has ever produced) has jumped genres is indeed an eye-opener. But anyone hoping for a welcome remedy to the proliferation of Saws, Hostels and the execrable Human Centipede: First Sequence may have to look elsewhere. For while Almodóvar considers his film to be ‘‘a horror without screams,’’ this isn’t strictly true. The ‘big reveal’ could easily be the product of Eli Roth’s (mis)reading of feminist theory. And that’s the closest you’ll get to a spoiler. No, a more appropriate description would be a horror without limits, for despite being set in a technologically advanced Toledo of 2012, this is sci-fi with the emphasis strongly on fi. A Hammer horror with scalpels and syringes.

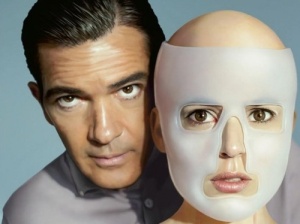

Antonio Banderas plays plastic surgeon Robert Ledgard, a man whose ambitious but unorthodox designs sandwich him firmly between the two doctors Frankenstein and Moreau. After discovering the possible benefits of transgenesis (fusing together human and animal genes) to create a more resilient skin, he experiments on his guinea pig, Vera (Elena Anaya). Vera, however, is a beautiful young woman who, for reasons unexplained to both her and us, is held captive in Ledgard’s mansion-cum-clinic and monitored, almost obsessively, via closed- circuit surveillance. Hers is, unsurprisingly, an unhappy existence: her self-harm wounds are re-sewn by the doctor (who rebukes her selfishness with the unblinking authority you’d expect from a psychopath) and she’s back to square one. Or not quite… There’s certainly something odd about this relationship- aside from the obvious Stockholm syndrome and bonding over the occasional skin graft- and, as the plot unfolds like a roll of gauze, we find that it only gets odder. You’d better brace yourself for when we reach the end.

In a story that jumps back and forth in time, and more than once politely asks that you save your questions for later, let’s just focus on the one scene that doesn’t give the game away. Robert is away on business, leaving housekeeper Marilia ( Almodóvar regular Marisa Paredes), to receive a surprise visit from her son, Zeca (Roberto Álamo); a scarred, bald-headed and noticeably tiger-costumed brute of a man who has strayed from the local carnival. He manipulates his mother into letting him into the house, before revealing his true intentions. He switches on the TV to show, right on cue, news footage of a jewellery shop heist. Wouldn’t you know it: Zeca’s oh-so- distinctive mugshot is caught on camera. Wouldn’t it be awfully neat if a spot of reconstructive surgery could fool la policía for just a little longer? But, Marilia explains, as the doctor is out, it has been a wasted journey. But Zeca has spotted some incriminating CCTV footage of his own: Vera stretching for yoga, oblivious to the fact that, downstairs, a man with a striped tail is licking ‘her’ on the screen. Here, as the shivers slip down the spine, we see that what we initially considered to be Almodóvar’s prize-winning entry for ‘campest Bond villain’ is in fact a genuinely unsettling savage. After a tortuous game of cat and mouse – he steals the keys and skulks from room to room, sniffing out his prey- he pounces on Vera and, to complete the analogy, becomes more animal than man. It is only upon Robert’s return that the true extent of the doctor’s obsession, and his burning need for revenge, is fully realised. To say anything more would spoil a storyline that, for all its initial promise of originality and, for the most part, twitching suspense, soon falls into a one-note farce.

Marilia is given the cumbersome task of informing Vera (and us) of Robert’s past; but chipping away at this big chunk of exposition whilst huddled around a garden campfire seems, in hindsight, a tad insensitive. After being struck by not one, not two but three personal tragedies, Robert’s misplaced sense of vigilantism spirals uncontrollably from a knee-jerk reaction to a carefully contrived counterstrike. Suddenly Job wants to play God. And so, with a serenely sadistic belief in ‘corrective justice’ that is taken a little too literally, Robert’s revenge isn’t a dish served cold; it’s a buffet.

Much has been made about the fact that this film marks Almodóvar’s reunion with his one-time muse, Banderas, (together for the first time since 1990’s Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!) but if only the pairing would’ve produced a more auspicious result. While the frenetic egotism of cinema’s ‘mad scientist’ is admittedly a relic from B-movies and comic book villains, the modern equivalent- the dead-eyed but driven professional psycho- also risks death by overexposure. Recent examples, the most notable (if unsurprising) being Patrick Bateman of American Psycho, have but replaced the hockey mask with a pinstripe suit. Banderas’ Ledgard wears a white lab coat.

The film really belongs to Anaya; half living doll, half loaded gun; it is she who carries the suspense, who begins the film as a mystery but ends as a…ah, that’s the closest you’ll get to a spoiler. But even a late exploration into her captivity serves only to illustrate her Jekyll-and-Hyde readiness to take refuge in her four walls mixed with her propensity for violence. Her cell becomes her sanctum becomes her cell again.

Ultimately, the film’s main flaw is in its tendency to tie all the loose ends haphazardly together. Resolutions are convenient, revelations convoluted. Without wishing to go into the details, Robert’s plan of retribution doesn’t seem suitable, let alone sufficient, closure. And while the final scene unfolds slowly and with a teasing uncertainty (perversely ending with the most gripping encounter thus far), it is overshadowed, moments earlier, by an ending that renders the previous ninety minutes into nothing but an extended exercise in ‘what if’? Improvident, but impossible. Satisfied, but not satisfying.

©D.Wakefield, 2011.