Well, isn’t this a love-in? Husband-and-wife directors cast real-life couple Paul Dano and Zoe Kazan to play onscreen twosome in schmaltzy shocker. There may be a precious symmetry in screenwriter Kazan writing a role for her partner, for him in turn to write one for her- but, having pilfered plotlines from Stranger than Fiction and The Twilight Zone episode ‘A World of His Own’, she has created a rather literal, and surely dangerous, take on intellectual copyright.

Well, isn’t this a love-in? Husband-and-wife directors cast real-life couple Paul Dano and Zoe Kazan to play onscreen twosome in schmaltzy shocker. There may be a precious symmetry in screenwriter Kazan writing a role for her partner, for him in turn to write one for her- but, having pilfered plotlines from Stranger than Fiction and The Twilight Zone episode ‘A World of His Own’, she has created a rather literal, and surely dangerous, take on intellectual copyright.

Dano plays precocious author Calvin Weir-Fields; with his breakthrough success a decade behind him, we find him cruelly inflicted by that most devastating and important disease of all, writer’s block. Living with his dog, Scotty, in an apartment as IKEA-white as the blank page slotted into the typewriter before him, his days are spent begging for a muse while lapping up the last scraps of applause for anniversary-edition audiences. After his therapist (Elliott Gould, barely onscreen for five minutes) suggests a writing exercise about Scotty, Calvin suddenly finds inspiration from a red-haired girl (Kazan) who can’t get enough of the dog- or his owner. Her name is Ruby Sparks: she’s endlessly smiling, enchantingly spontaneous… and she doesn’t exist. Despite (or rather, due to) living purely in Calvin’s thoughts, serving only to transform his dreams into tomorrow’s chapters, Ruby is the perfect girl. Every night she declares her love for him, and every morning he rushes straight to the typewriter. After a few days of inexplicably finding items of women’s clothing scattered around his house like a trail of crumbs, Calvin wakes one morning to find her, exactly as he had described her, standing in his kitchen.

Ruby sees Calvin not as her maker but as her soulmate, as stunned by his astonishment as he is of her appearance. The fact that other people can see and hear Ruby only makes Calvin question his sanity further. Yet it seems the only way of convincing his sceptic brother, Harry (Chris Messina), is to invite him to see for himself. In doing so, the two men stumble upon an incredible discovery: Ruby has strangely, but spectacularly, sprung to life from the seeds of Calvin’s imagination. Whatever he writes about Ruby almost instantaneously takes effect. In the hands of a conceited creator, such omnipotence is irresistible, and, after briefly dismissing the ensuing pangs of guilt, Calvin soon finds himself in a relationship that he can control at the (keyboard) click of his fingers…

Mistakenly pitched as a romantic comedy, Ruby Sparks, like its titular toy, undergoes something of an identity crisis. How can a film that spouts such syrupy nonsense as ‘‘Falling in love is an act of magic. And so is writing’’ attempt to wring laughs from the malicious streak of misogyny that suffuses almost every scene? Ruby is created, essentially programmed, only to please Calvin; so of course she would be attractive, a great cook- and, most importantly, intellectually inferior to him. He resents her independence, so reduces her to a needy and insecure wreck who clings and cries like an infant. When this too becomes unbearable, he ‘grants’ her freewill but immediately misses the adulation and so reverts, literally, to type. This cycle continues until culminating in the film’s most repugnant scene; Calvin demonstrating his control over Ruby by making her scream all that she finds desirable in him, before collapsing and practically melting like the Wicked Witch. Such cruelty typifies his relentless narcissism (as both an author and a lover), yet it’s a trait he unfathomably shares with his creation. But then again, Ruby isn’t entirely of his own conception: her assembly-line whimsy and exasperating impulsiveness make her the most literal interpretation of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl trope yet. Despite Kazan’s aversion to the term being applied to Ruby, her attempt to emulate the charm of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and (500) Days of Summer, after Zooey Deschanel had not only embodied but emphatically buried the stock character through her performance in the latter, does not invite flattering comparisons.

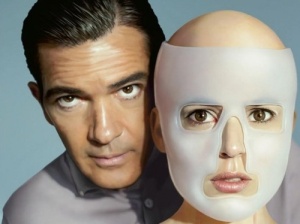

Calvin’s trademark misanthropy is practically excused by the sheer unpleasantness of his supporting cast. From his New Age parents, (Antonio Banderas, slightly oblivious to his surroundings, and Annette Bening, rehashing her role in The Kids Are All Right) to his shady agent (Steve Coogan), not a single character warrants our interest- or even their inclusion to the plot. Rarely has a film (especially a rom-com) required you to rank the necessity of every performance, but here the votes are undeniably tied between the leading couple themselves. With his permanently perplexed expression of a boy caught with his hand in the cookie jar, unsure whether to expect a punishment or a reward, Dano has found a snug niche in the arm-flailing, over(re)acting Chandler Bing school of smarm. And while there’s a hint of the clumsy cuteness of a younger Kristen Schaal in her turn as Ruby, Kazan’s script bears an uncomfortable sadomasochism in its portrayal of a woman suppressed by sexist ideals.

Ruby Sparks inhabits a place of wanton wish-fulfilment (although, for a writer, Calvin has a startling lack of imagination), peerless predictability and where conflict is caused, and resolved, with the frantic pressing of a typewriter. While the film’s obsession around the object itself evokes Frank Lloyd Wright’s famous aphorism about dangerous weapons (a finger hovering above the delete key would presumably be less dramatic), the wish for Calvin to type the film’s ending considerably sooner sadly goes unheeded.

©D.Wakefield, 2012.